One Week Left!

When I started this project, my first goal was to put together a list of women who applied for pensions between 1866 and 1892. My total is somewhere around 625—and if fold3 would update its database every once in a while, and Ancestry let me limit pensions by year, it’d be much bigger. Anyway, since the Archives only allow a certain number of pulls a day, and I’m only here for five weeks, I knew I wasn’t going to be able to pull all 650, so I printed out a list, highlighted every other name, and hoped that this would be a good random sampling. And if it wasn’t, well, in five weeks I can pull a maximum of 400 pensions, and since 625 divided by 2 is 312.5, I have some wiggle room. One week, to be precise. Next week.

Which is why yesterday there was no post. I know I can always come back to D.C. this summer, or come up in the fall, but I want to get as much done now as possible. So yesterday was planning. And here is the to-do list:

I have time for 72 more pension pulls. Go back through the rejection slips (you know, I got 9 yesterday. 9!! And Harriet Stinson Pond is not an officer from a Kentucky regiment! Geez…), and decide which ones I want to/can request again. Then, go through the master list and see if I missed anyone I particularly wanted to pull—blacks, nuns, women who are particularly well-documented. Random sampling for the rest of the list. DONE

Legislation has the list of Special Acts I want to see. Pull those, go through. Make sure to check for women not on the list. Also go through the other file related to the 1892 Act.

Put together a list of the Congressmen on the Committee on Invalid Pensions and see if they have papers here or at the LoC. I have a few letters between the WRC and various Congressmen, so I know the correspondence is there, it’s just a matter of finding it.

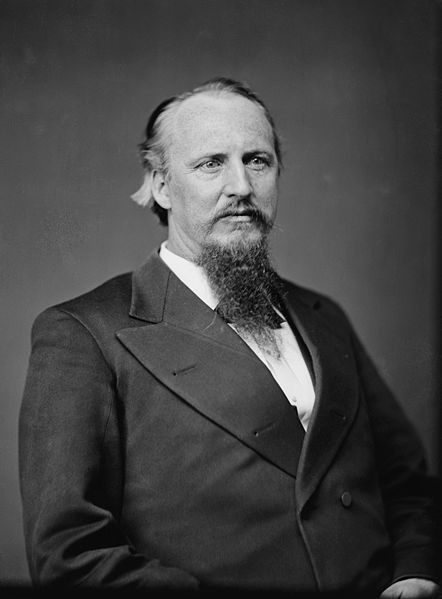

Check to see if the LoC of the Archives have anything on the WRC women on the National Pension Committee: E. Florence Barker, Kate B. Sherwood, Lydia A. Scott, Mary A. Logan, Sarah E. Fuller, Clara Barton and Annie Wittenmyer (technically she’s not on the Committee, she’s the WRC president, but she’s endorsing so many applications she might as well be on the committee). Also, see if there’s anything on James Tanner—Tanner was Commissioner of Pensions in 1889 and had very liberal policies about who he gave pensions too. After he exceeded the Bureau's budget and had to resign, he set up a private law firm, specializing in pensions. In 1892, he offered to help nurses obtain pensions. Legally, he couldn’t ask for a fee for his work; it all had to be pro bono. But, he still offered, and a significant number of the nurses on my list have power of attorney papers giving him the ability to prosecute their case, or affidavits and forms with his firm’s stamp on it. If he has papers, they could shed some light on how these women found out about the pensions, the process of applying, and why so many women chose him to act for them.

If there’s time, go through the microfilm of letters to/from the Pension Office from 1860s to 1890 and see if there are letters relating to the project (they have the letters from 1890 onward nicely indexed by subject and sender, but not these—why?!).

A number of my nurses lived here in D.C. for a time, like Susan Edson and Caroline Burghardt (I actually live a block and a smidge from one of them—her home is now a Bertucci’s…). Check the D.C. historical society and see if they have files on these women. Chances are slim, since the last time I checked they were looking for a new head librarian, and have been closed for nearly a year, but you never know.

Finally: if the weather ever cools down enough to leave air-conditioned comfort and permit long walks, I want to go to Arlington. A few of my nurses are buried there, and I’d like to see them and get pictures for their files.

So, no problem, right? Right.

One more week, guys! Keep your fingers crossed it’s a good one!